Morning Comrades.

I had written a piece on this sometime in 2022 for the patreons of this substack and considering the events of this week, I wanted to share this with everyone with an amended text.

For all the obvious reasons.

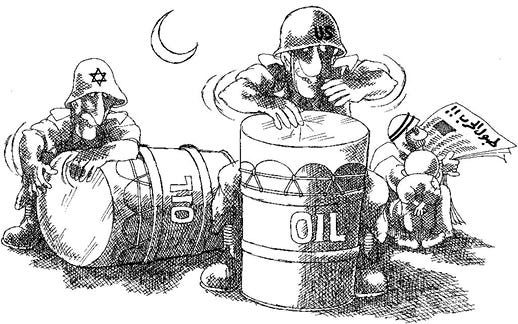

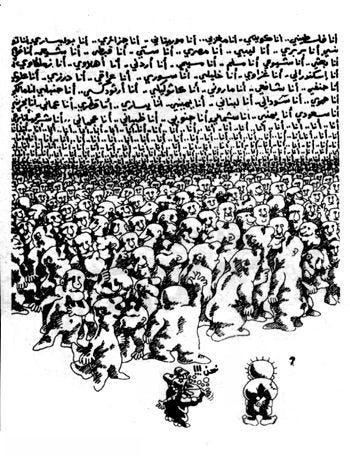

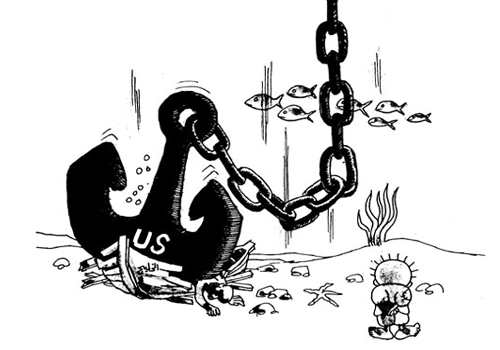

The comics and related arts (cartoons, graffiti, illustrated posters and signs) have always played an important role in shaping public protests. From the French Revolution to the recent Arab Spring revolutionary wave of demonstrations and protests, these visual means have stood out thanks to their ability to transmit their message quickly, clearly and descriptively. Often these means have enabled the masses to see their social, economic and political reality in a new and critical light. Social, economic and political cartoons are a popular tool of expression in the media. Cartoons appear every day in the newspapers, often adjacent to the editorials. In many cases cartoons are more successful in demonstrating ideas and information than are complex verbal explanations that require a significant investment of time by the writer and the reader as well. Cartoons attract attention and curiosity, can be read and understood quickly and are able to communicate subversive messages camouflaged as jokes that bring a smile to the reader's face. Cartoonists are in fact journalists who respond to current events and express their opinions clearly and sometimes even scathingly and satirically. They translate political, social and economic issues into locally familiar cultural symbols, as well as using symbols that are universally recognized.

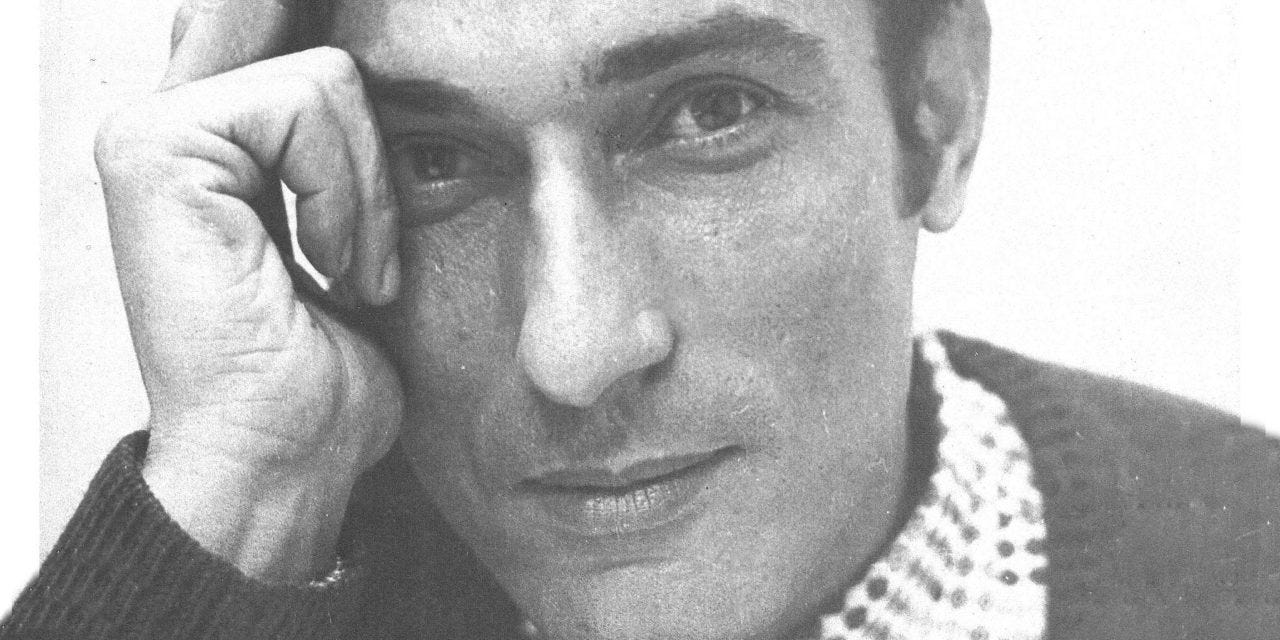

The Palestinian cartoonist Naji Al-Ali was considered one of the most prominent cartoonists in the Arab world. He was assassinated outside the London office of Kuwaiti newspaper Al Qabas in Ives Street on 22 July 1987- Naji al-Ali was subsequently taken to hospital and remained in a coma until his death on 29 August 1987. To this day it is still semi-unclear who carried out the assassination on whose orders, but most, if not all signs point to the Mossad, specifically, a double agent that publicly claimed to be working for the PLO at the time.

Al-Ali’s cartoons influenced millions of people throughout the Arab world. His cartoons were not intended to entertain the readers, but rather always conveyed political messages. In addition to expressing his personal views, they were sarcastic and daring reflections of the feelings of the Palestinian refugees. The loss of Palestine was the main inspiration for his cartoons. Therefore, he dedicated most of his cartoons to the suffering of his people, especially the poor living in the refugee camps. Some of his work was also dedicated to the oppressed people of the Arab world as well as oppressed people worldwide. Although most of his cartoons were very pessimistic, some were full of hope, dreams and aspiration for a better life for the Arab people in general and the Palestinians in particular.

Al-Ali addressed taboo issues while avoiding the strict censorship imposed on Arab newspapers. His cartoons were simple, clear and easy to understand and were often published next to editorials with political messages. The cartoons spoke to and about ordinary people. His readers waited eagerly to see his drawing on the last page (which became their front page) of many Arab dailies in Lebanon, Kuwait, Tunisia, Abu-Dhabi, Egypt, London and Paris. On the other hand, many Arab countries prohibited him from entering and banned his cartoons from their local newspapers. Al-Ali criticized the injustice done to the Palestinian people by Israel. He scathingly criticized the Arab regimes as well as Arafat’s leadership for their submissiveness and corruption. His sharp political and social criticism embarrassed many Arab leaders, who became his enemies and tried to silence him by censoring his work. During his lifetime he received hundreds of death threats and ultimately was assassinated in 1987. Naji Al-Ali drew more than 40,000 cartoons, but he was famous mainly for Handala, the little Palestinian boy who stands on the sidelines watching the injustices done to his people. Handala became Al-Ali’s trademark and a major icon of Palestinian iconography.

Naji Al-Ali was born in 1937 in the northern Palestinian village Al-Shajara, situated between Nazareth and Tiberius. His family, like 750,000 other Palestinians, was uprooted during the Nakba (the catastrophe) in 1948, and his village was destroyed along with another 480 Palestinian villages. Al-Ali’s family settled in the Ein al-Hilweh refugee camp near Sidon in south Lebanon when he was ten years old. The Nakba and life in the refugee camp had a tremendous influence on him and served as the main inspirations for his work. He began drawing at school in the refugee camp and received encouragement from his teachers. He witnessed the constraints imposed on Palestinians by the Arab countries serving as their hosts. His refugee experiences made him swear to immerse himself in politics and serve the Palestinian cause. His first drawing, "a hand holding a torch ripping a refugee tent," represents his commitment to the Palestinian revolution.

He subsequently moved to Beirut, where he lived in the Shalita refugee camp and worked at various industrial jobs. After qualifying as a car mechanic in 1957, he went to work in Saudi Arabia for two years. In 1959 he returned to Lebanon and joined the Arab Nationalist Movement (ANM) established by Dr. George Habash and his university collogues as a protest against the defeat of the Arab regimes in 1948. Al-Ali was expelled from the ANM four times within a year for lack of discipline. Together with his some ANM comrades he published a handwritten political magazine called Al-Sarkha (the cry), which appeared for two years (1960-1961). He enrolled in the Lebanon Academy of Art in 1960, but was unable to continue his studies there as he was imprisoned many times for taking part in political activities in the Palestinian camps. He began drawing on the walls of the Lebanese jails as a form of political expression.

He later moved to Tyre, where he worked as a drawing instructor at the Ja’fariya College. The turning point in Al-Ali’s life as a political cartoonist came in 1961, when Palestinian novelist Ghassan Kanafani discovered his talents. Al-Ali's first drawings were published in the Al-Hurriya (liberty) magazine together with an article written by Kanafani. In 1963 Al-Ali moved to Kuwait as a result of Lebanese constraints imposed on Palestinian refugees and also due to the great demand for professionals in the Gulf States at that time. He married in 1964 and continued living in Kuwait, where he worked for the Arab nationalist weekly magazine Al-Tali’ah (the forefront). Feeling that freedom of speech was being limited at the newspaper, in 1969 he introduced Handala to his readers for the first time. During his time in Kuwait he made several visits to Lebanon. In 1974 Al-Ali moved back to Lebanon and began working at the Lebanese newspaper AlSafir (the ambassador). He was shocked by the major trends sweeping the Palestinian refugee camps at that time. He claimed that prior to 1973 the refugee camps had been united and had clear goals, but due to the oil money brought by the PLO into the camps they had become chaotic armed jungles. He accused the Arab regimes as well the PLO leadership of corrupting the young generation of Palestinians.

Al-Ali witnessed and scathingly criticized the battles within the Palestinian refugee camps, the split in the Arab world after the 1973 war and the civil war in Lebanon that broke out in 1975. He called for unity among Christians and Muslims and for improving the status of women in the Arab world. He criticized corruption, lack of democracy and the widening social and economic gaps in the Arab countries.

During the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, Al-Ali was detained for a short time by the Israeli army. That traumatic war made him once again move to Kuwait in 1983, where he worked at the Al-Qabas newspaper. He was frequently detained by the Kuwaiti police, and in 1985 a decision was made to expel him for good. He decided to settle in London and work for the international edition of the Kuwaiti newspaper Al-Qabas. Two years later he was shot in the head outside the London offices of Al-Qabas. He was 49 years old when he was killed. Two weeks before his assassination he received threats from prominent Fatah leaders, who warned him not to go too far with his political criticism of Arafat. In one of his cartoons he depicted Arafat as a dictator willing to make humiliating compromises.

Thank you for your time, attention and support and I wish you all a peaceful weekend.

Yours, without compromise,

V.