Art In Service Of The Revolution

The Mexican Muralists

Morning Comrades!

Once again, we are wrapping up the week with an instalment in this series and this time we are heading to Mexico, a place extremely dear to my hear and a place that has luckily welcomed me with open arms.

Logically, when speaking about art in the service of the revolution and Mexico one immediately thinks of Frida Karlo but that is not someone we are talking about today. Rather, we are going down the rabbit hole known as the Mexican Muralists.

Mostly, when one speaks of this movement in art the Los Tres Grandes or The Three Great Ones are immediately spoken about: Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Their work and contribution is without a doubt the most well known, but I also want and have to mention these comrades that the male dominated art world all too-often likes to ignore and are for you to get into:

Aurora Reyes Flores, Elena Huerta Muzquiz, Rina Lazo and Fanny Rabel.

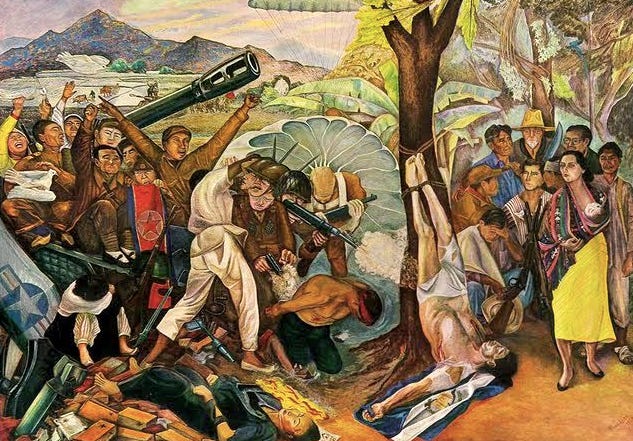

Strikingly different in environment from Socialist Realism, the Mexican Muralists portray capitalist society, and the oppression of the working class within it. Both forms of art recognise the educational role of art, and the Mexican Muralists put this into practice by painting enourmous murals on the most public of buildings in order to reach and communicate effectively to the largest possible audience. One strong addition in the style of the Mexican Muralists is portraying not only the importance of social activity (which it does on a much more grandiose scale), but making abundantly clear the importance of material conditions, making for a more rounded practice of theoretical marxism; i.e. historical materialism. Both forms of art see the future as full of hope and optimism, they contrast however in their outlook on the present. The Socialist Realists, in painting about socialist life, are usually optimistic, while the Muralists who portray life under capitalism, paint primarily very bleak and heartbreaking works – as Sergi Eisenstein said of the paintings of Jose Clemente Orozco: "... the nerve of reality is fixed as though with a nail to the wall."

A new national identity

In the immediate years following the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920), the newly formed government sought to establish a national identity that eschewed Eurocentrism (an emphasis on European culture) and instead heralded the Amerindian. The result was that Indigenous culture was elevated in the national discourse. After hundreds of years of colonial rule and the Eurocentric dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, the new Mexican state integrated its national identity with the concept of indigenismo, an ideology that lauded Mexico’s past Indigenous history and cultural heritage (rather than acknowledging the ongoing struggles of contemporary Indigenous people and incorporating them into the new state governance).

José Vasconcelos, the new government’s Minister of Public Education, conceived of a collaboration between the government and artists. The result were state-sponsored murals such as those at the National Palace in Mexico City.

Why murals?

Rivera and other artists believed easel painting to be “aristocratic,” since for centuries this kind of art had been the purview of the elite. Instead they favoured mural painting since it could present subjects on a large scale to a wide public audience. This idea—of directly addressing the people in public buildings—suited the muralists’ Communist politics. In 1922, Rivera (and others) signed the Manifesto of the Syndicate of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors, arguing that artists must invest “their greatest efforts in the aim of materializing an art valuable to the people.”

More Background

Compared to other Communist movements, the Communist Party of Mexico or PCM (Fondo Partido Comunista Mexicano) was judged weak in terms of membership and leadership in the early 1920s. Inspired by the example of the Russian Revolution, Mexican Leftists saw art as an important way of spreading the message of the PCM in the early years, be it through art or propaganda. The art would explain the party’s message and attract converts. The lives and work of the Muralists captured the imaginations of the public and were frequently covered by the newspapers. The artists (especially Rivera) were deemed politically unreliable but useful to the party. They edited the Communist newspaper El Machete for a time. The Mexican governments’ views of the PCM veered from wary collaboration to outright hostility, depending on the party in power. In 1929 the government banned the PCM and closed El Machete, which continued for a while as an underground operation.

Rivera was a problem for the PCM. He was the most prominent Mexican Communist, with an international reputation and wide popular appeal but he was wilfully independent and accepted mural commissions from the government, which was sporadically hostile towards the PCM. When Rivera left the PCM, Frida Kahlo, who was married to Rivera, left the PCM with him. The PCM undertook its other disciplinary procedures, expelling Siqueiros for inappropriate behaviour, risking revealing secret information about the now-banned party, plus various moral and financial infractions. Communist artists subject to hostile government action included Sergei Eisenstein and Tina Modotti, both of whom had to leave the country.

In comes the associated Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios (LEAR). Like the PCM at this time, LEAR was a banned organisation when it was formed, only later becoming legal. Its journal Frente a Frente included much Leftist and social realist art in the form of prints and photographs by LEAR members. Much visual material was propaganda explicitly dedicated to exulting collectivism and eschewing “the mystique of the individual”. In 1935 LEAR members persuaded the government to unban the PCM, El Machete and LEAR. A 1936 group exhibition of art organised by LEAR included amateur art and even politically sympathetic commentators described the display as a mess and criticised the standard of art. Steering a course between political orthodoxy and artistic accomplishment was an impossible task.

An article in Frente a Frente (May 1935) by Siqueiros was critical of Rivera’s Rockefeller Center fresco (1934). - Rivera had painted a massive mural in New York that included Lenin, upon seeing it, Rockefeller demanded him be removed from the mural, which Rivera declined, and the mural was destroyed. It led to a public debate between the artists later that year. They were divided on the appropriateness of murals as a revolutionary art form. Siqueiros – perhaps piqued by Rivera’s greater success – averred that murals were overrated as a political tool and that art should be international in character and closer to Socialist Realism than Rivera’s hybrid, which incorporated Modernism and native Mexican art. Rivera asserted that he wished to record the beauty and individuality of Mexican life in his art and that this was not incompatible with Communist principles. Siqueiros was pro-Stalin and Rivera pro-Trotsky. Deep enmities remained between the two painters for years afterwards.

Siqueiros became so involved in politics that he neglected art. He fought in the Spanish Civil War, as did Modotti. Rivera played a pivotal role in arranging for Trotsky’s successful petition for political asylum in Mexico. Trotsky arrived in Mexico in 1937 and lived in the Riveras’ guest house for a time. Despite public and private support between the men, there were political tensions. Ultimately, Trotsky and Rivera’s alliance ended due to political differences in early 1939. Siqueiros and artists Luis Arenal and Antonio Pujol worked with NKVD in a plot to kill Trotsky. On the night of 24 May 1940 the trio broke into Trotsky’s house, failed to find the elderly dissident and – apparently inadvertently – injured his grandson. Months later an unrelated individual assassinated Trotsky.

Perhaps the most valuable service the FCM, TGP, LEAR and their various publications achieved in the arts was to present a warning of the dangers of fascism and raising funds for the Spanish anti-Falangists. Later, their activities would help the refugees who fled the fall of Spain and Nazi-occupied Europe.

Again, as with the other dispatches in this series, this serves an introduction and introduction only. The depth of this particular rabbit goes deep and I can only recommend jumping in.

As always, thank you for your time, attention and support.

Yours, without compromise,

V.